Why your RBAC roles aren't actually roles

CEO / Founder

Most security teams understand Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) basics: map permissions to roles, assign users to roles, and you can control access. Simple enough. Well, except that every tool you use implements RBAC slightly differently, so you do need to think about it: who should be our GitHub CI/CD Admin? What’s the difference between a Vercel Member, Developer, and Contributor?

But there's a fundamental confusion that makes RBAC implementations difficult to manage: we keep using job titles as access roles. You should never encounter a "Growth Hacker" or "Chief Happiness Officer" in your access control system, even though they might be in your org chart. Your job title makes a bad RBAC role.

Roles describe what you do, not who you are

A role in RBAC should represent what someone actually does in your environment. Your job title, on the other hand, is about reporting structure, compensation bands, and career progression. It's your position in the corporate hierarchy, not your function.

Roles like "Customer Support" or "IT Admin" might make sense in both contexts, because they not only describe specific job functions, but are also tightly coupled to typical tasks someone in that position needs to accomplish. These roles are the exception rather than the norm.

Take a "Product Manager" instead. A Product Manager working on billing needs access to Stripe and support tickets, but a Product Manager working on Android needs access to app builds and bug reports. Same title, completely different functional needs. If you create a single "Product Manager" role, you're forced to either over-privilege everyone or create dozens of variations like "Product Manager - Billing" and "Product Manager - Android." What you actually want is a role that describes the billing team or the Android team.

What makes this worse is that job titles change constantly — should changing your job title in Workday to “AI Engineer” really change access? — and what those jobs actually entail evolves even faster. In today's flexible organizations, people wear multiple hats that don't fit neatly into traditional role definitions. (Seriously, what is a "GtM Engineer"?)

How we ended up in this mess

When organizations first adopt RBAC, they might go through a "role mapping" exercise to consolidate permissions into common workflows. Too often, IT leads this process without sufficient business context. It's easy to map existing permissions to a role that exists in an org chart, like "Marketing Manager," without asking if that's really the right access control boundary — or worse, a “Vendor” or “Partner”.

Being too generic doesn't help either. An "Admin" role doesn't actually mean anything. And "Data Reader" could represent 10 different job titles with completely different needs. You can't create meaningful roles without understanding what work actually looks like.

This gap has become glaringly obvious in the past few months as we rush to deploy AI agents: just like humans need appropriate roles, agents need appropriate OAuth scopes. We're struggling with the same “role explosion” problem: it’s unrealistic to create hundreds of OAuth scopes, and granting broad access is risky. We never learned to think functionally about access control for humans, so we're making the same conceptual mistakes with agents.

Making RBAC work for you

So, how should you think about adopting RBAC?

First, work with business teams to define roles. Every organization is different, and there's no one-size-fits-all approach. Ask business teams: who does the same tasks? Who works together on this specific type of work? People with completely different job titles might end up with identical access to systems.

Good functional roles sound boring and obvious: “Blog Publisher”, “Invoice Processor”, or “Customer Data Viewer”. Many people across different teams might need to publish blog posts, so they all need access to the publishing platform. If your role name requires a hyphen or sounds like it belongs on a LinkedIn influencer's bio, you're probably doing it wrong. Keep definitions simple enough that non-technical stakeholders can understand — and request access to — them. Taking the time to define roles that are clear and have sufficient context, as this will save you time later.

Use fewer, broader roles rather than overfitting to every scenario. When you have hundreds of roles, you've created a system that nobody understands. Role mapping turns into “role mining” or even “role engineering”. Role sprawl isn't just annoying — it's impossible to debug when something goes wrong if you can't tell why roles exist, who should have them, or how two similar-sounding roles differ.

Start by only defining roles that you actually need to restrict. Split out the riskiest permissions into roles that need to be more tightly controlled, and keep a reasonable base set of permissions for everyone else. You can start with basic permission levels that apply to any resource, like Reader, Writer, and Admin. These boring old roles exist because they actually work — your cloud provider didn't pick them by accident. Don’t define roles for the sake of it, but as you have a need to enable new users and restrict sensitive permissions. Accept some over-privilege to avoid the administrative hell of managing hundreds of hyper-specific roles. You'll have exceptions regardless, so spend your time building a decent exception process instead of trying to create the perfect role taxonomy.

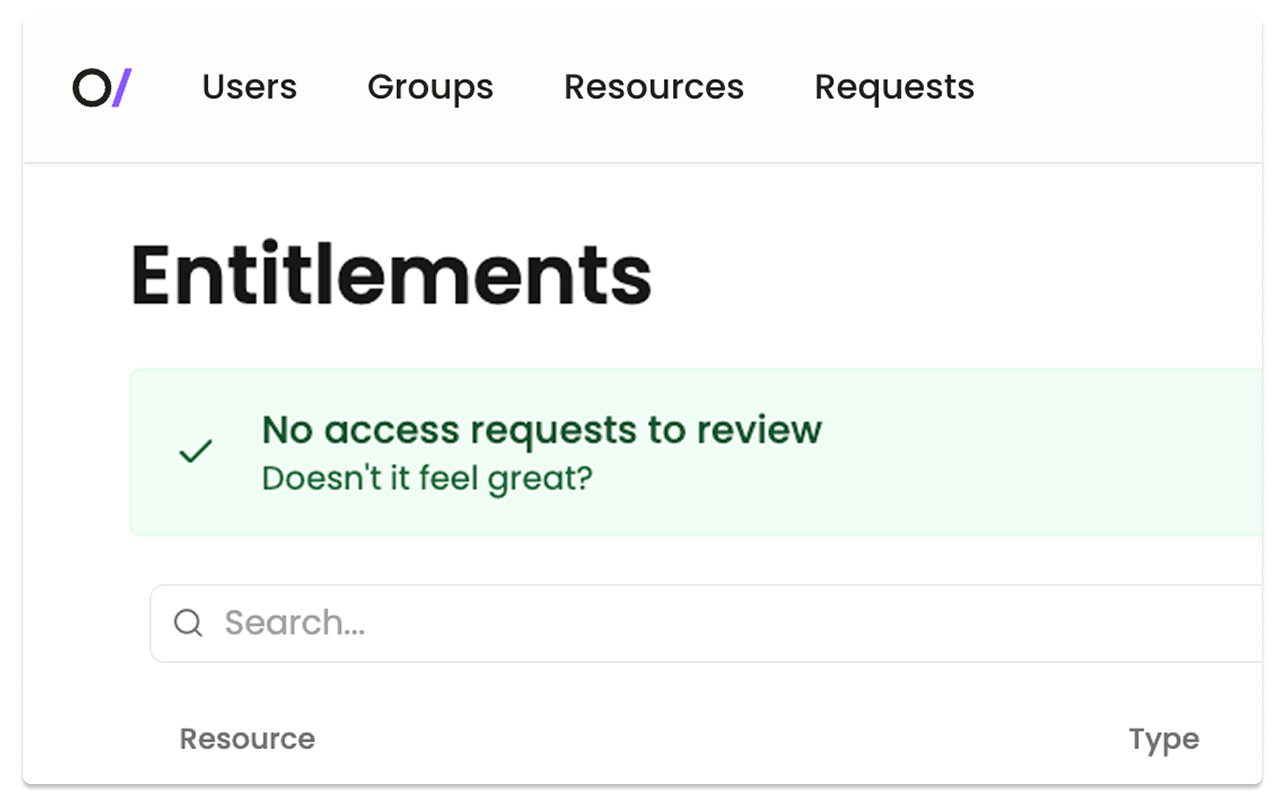

Plan for ongoing maintenance. This is the part that often gets left by the wayside. Roles need regular review and updates — you can even do this at the same time as your user access reviews! Instead of just checking if Bob should still have the Admin role, also review what the Admin role can actually do and whether that still makes sense. Roles have a nasty habit of scope creep, quietly accumulating permissions over time as teams request access to new tools and systems. Check periodically that your "Viewer" role can't actually modify data. Audit role capabilities, not just role assignments.

Mix and match your access models

Real organizations are complex, people wear multiple hats, and business needs change faster than security can keep up. The issue isn’t RBAC, it’s how organizations implement RBAC.

Most organizations don’t implement a “pure” access control model. Instead, they blend RBAC for stable business functions, ABAC for context-dependent decisions, and other approaches as needed. Rather than forcing everything into roles, let attributes be attributes — someone's department is useful as an attribute for access decisions, not as another role to manage.

Keep RBAC functional

We struggle to maintain access controls because we've designed them around what people are called rather than what they actually do. Job functions matter for access control, but they're just one piece of the puzzle. Where you're working from, what time it is, and who you're collaborating with often matter more than your title.

At the end of the day, RBAC is an imperfect tool. Design a sane and maintainable set of groups, focus your security efforts on the riskiest permissions, and build processes to handle the inevitable exceptions and changes coming your way.